If AI Can Do Your Job With a Better Prompt, What Were You Really Doing?

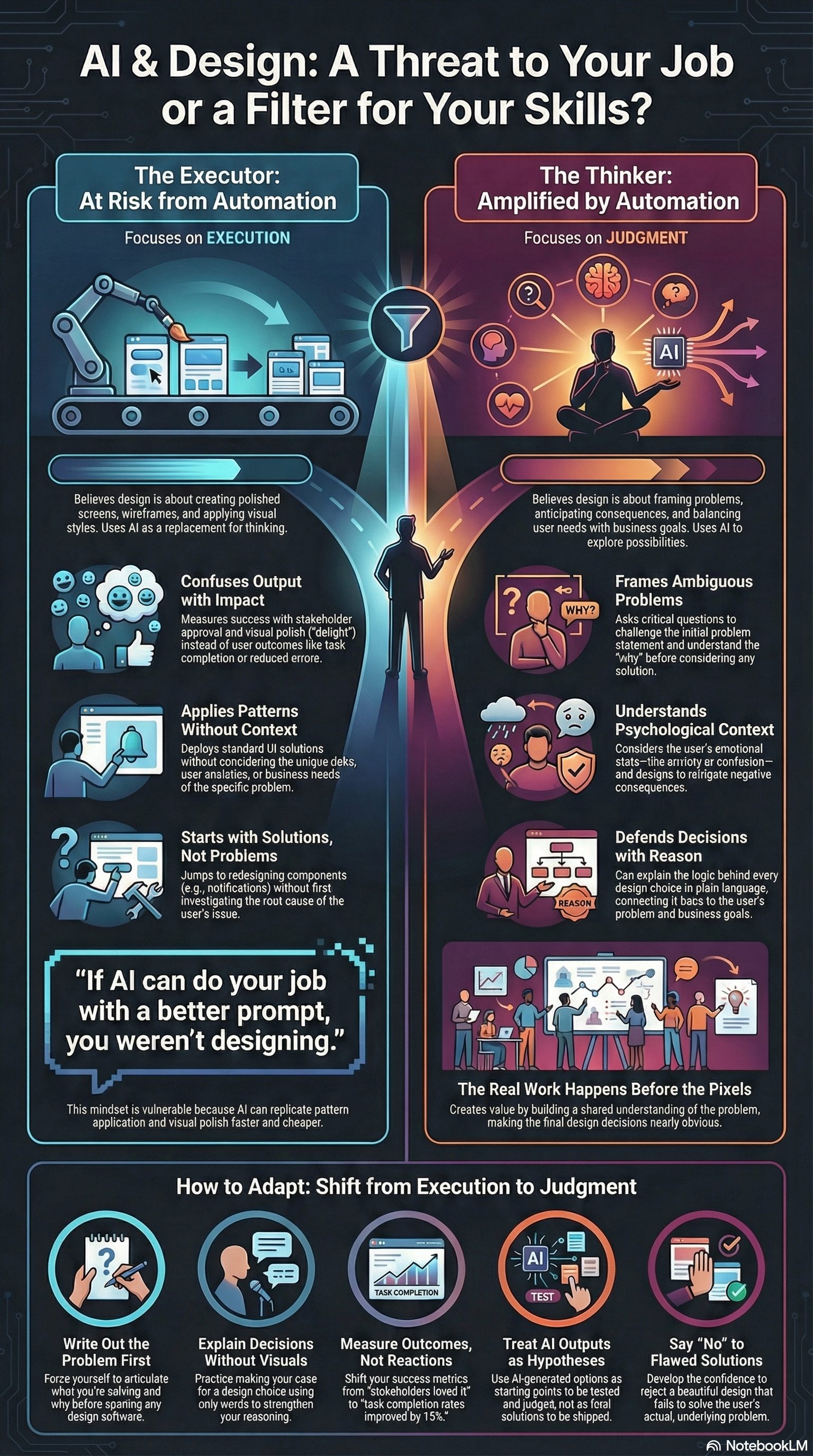

AI isn't threatening design as a discipline. It's exposing designers who confused execution with thinking. Here's what separates real design work from what machines can now replicate.

Every few years, the design profession faces an existential panic. First it was templates. Then no-code tools. Now it's AI, and the fear feels more visceral than ever.

If a machine can generate screens, user flows, and interface copy in seconds, what exactly is left for designers to do? It's a reasonable question, and the speed of AI advancement makes it feel urgent.

But here's the uncomfortable truth. AI is not threatening design as a discipline. It's threatening designers who were already operating on thin value. And it's not replacing them by doing something radically new. It's replacing them by making execution cheap enough to reveal who was never really designing in the first place.

The Wrong Model for Thinking About Threats

Most designers assume AI threatens what they can see: the screens they create, the wireframes they iterate on, the visual styles they define, the UI patterns they assemble. That's why the panic centers on tools and capabilities.

But historically, tools don't eliminate professions. They compress the lowest-value layer of work and expose what was actually valuable all along.

Spreadsheets didn't replace financial analysts. They replaced manual calculation and revealed that analysis and judgment mattered. CAD didn't replace architects. It replaced drafting and made clear that spatial thinking and client collaboration were the real work. Code completion didn't replace programmers. It replaced boilerplate and showed that system design and architectural decisions were always the core skill.

AI is doing the same thing to design right now. It's automating repetitive execution, first-draft generation, and obvious pattern application.

Which leads to the harder question most designers are avoiding: If AI can generate something close to your output in seconds, what were you actually being paid for?

Two Approaches to the Same Tool

Consider how two different designers might use AI in their workflow.

Designer A prompts the AI with "a modern onboarding flow for a healthcare app" or "a dashboard for patient monitoring." They review the options, select the cleanest execution, polish the visual details, and present it with confidence. The work looks professional. The delivery is fast.

Designer B starts differently. Before touching AI, they ask: Who in this experience is anxious, and why? What decision feels irreversible to the user? What mistake are they afraid of making? What happens if they abandon this flow halfway?

Only after working through these questions do they use AI, prompting it multiple times to generate options they can evaluate against the problems they've defined. They reject most outputs and modify what remains based on constraints the AI couldn't know about.

The output from both designers might look similar in a portfolio. But the difference in process is profound. One uses AI as a replacement for thinking. The other uses it to explore possibilities after the thinking is done.

The difference isn't taste. It's judgment. AI amplifies both designers, but only one has something worth amplifying.

What Designers Are Actually Hired to Do

Design is described and evaluated visually, but its real function is invisible. Organizations hire designers to frame ambiguous problems, decide what not to build, balance competing pressures from user needs and business constraints, and anticipate consequences that won't be obvious until after launch.

The screens and prototypes are artifacts of those decisions. They're evidence of thinking, not the thinking itself.

Here's a simple test: If AI can do your job with a better prompt, you weren't designing. You were executing someone else's decisions, even if that someone was just convention.

The Weak Signals AI Will Expose

Certain patterns have existed in design work for years but were easy to hide behind tool proficiency and visual polish. AI is removing those hiding places.

Confusing Output With Impact

Designers celebrate visual polish and talk about creating "delight" without connecting it to measurable outcomes. They measure success through stakeholder approval rather than whether users can accomplish what they came to do.

Think about a team that redesigns a dashboard beautifully. Clean typography, thoughtful white space, contemporary colors. They showcase it to enthusiastic applause. Three months later, task completion rates have dropped and error rates are up. When questioned, the response is: "But users loved the new look."

No one measured whether users could complete tasks more effectively. The design optimized for looking good in screenshots rather than working well in practice.

AI can generate polished interfaces instantly. If your primary contribution was making something look professional, AI just surpassed you at a fraction of the cost.

Applying Patterns Without Understanding Context

Some designers have become very good at pattern recognition. They know the conventions and can execute clean, familiar interfaces quickly. But they apply the same solutions across wildly different contexts because they're not reasoning about the problem.

Imagine using an identical onboarding flow for a consumer fintech app, a healthcare application, and an internal enterprise tool. Each has a completely different risk profile. Fintech can be casual and fast. Healthcare needs to slow users down at critical decision points. Enterprise tools must respect that users are already frustrated.

But the designer uses the same pattern in all three cases because "users expect this pattern."

AI is excellent at recognizing and applying average patterns. If your design logic is interchangeable and context-free, AI will match it cheaply. What AI can't do is adapt general principles to specific contexts with specific constraints and risks.

Starting With Solutions Instead of Problems

A problem arrives as "We need to reduce appointment drop-offs in our scheduling system." The immediate response is redesigning reminder notifications. New visual treatments, different timing, push versus email versus SMS.

But better questions come first. Are appointments dropped because users forget? Because they're anxious? Because they don't understand the cost? Because they can't arrange transportation? Because cancellation is too complicated?

Only one of those problems is solved by better reminders. The others require completely different interventions, and some aren't design problems at all.

AI assumes the problem statement you give it is correct. It will happily optimize for the wrong constraints. Human designers must challenge the problem definition. If you're not doing that, you're just decorating assumptions.

Being Unable to Defend Decisions

When a designer can't explain why they made a choice beyond "it felt right" or "that's what other apps do," it reveals that no real decision was made.

A stakeholder asks why a particular step in a flow is mandatory. The response: "It's standard UX practice. This is how onboarding flows work." The conversation ends, but not because the answer was satisfying.

AI can generate plausible-sounding explanations for any design choice. If you can't defend a decision better than a language model can fabricate a justification, your authority collapses.

What Strong Designers Do Differently

Strong designers use AI to explore possibilities, not to make decisions. They generate multiple directions knowing they'll kill most of them. They slow down at moments where consequences are high. They can explain decisions in plain language and design without screens when needed.

They don't fear AI because AI amplifies judgment, and judgment is exactly what they bring.

Picture a designer walking into a healthcare product review without mockups. Instead, they describe what happens in the user's mind at a specific moment. The fear of making a mistake with medical consequences. The hesitation from not understanding clinical terminology. The mental cost of a wrong click when you're already anxious.

They paint a picture of the psychological context the interface must work within. They identify where the system needs to slow users down versus speed them up. They articulate which decisions feel permanent to users, even if technically they aren't.

Only after establishing this shared mental model do they open their design tool. At that point, the design decisions are almost obvious because everyone understands the actual problem.

This designer might use AI later in the process. But the value was created before any pixels existed. AI can't replace that sequence, but it will punish designers who skip it.

The Uncomfortable Truth About the Industry

Design education teaches tools and portfolios. Students graduate knowing software and how to make work photograph well. Hiring evaluates aesthetics and presentation skills. Social media rewards what looks impressive in static images.

The result is an industry full of designers who look competent in exactly the ways that are becoming automated. They can execute clean interfaces and know the patterns, but many are strategically fragile because they've optimized for signals AI can now replicate.

AI didn't create this problem. It made it impossible to ignore.

If This Feels Uncomfortable, Use It

If parts of this feel too close to your own work, that discomfort is information. It's an opportunity to be honest about which parts of your practice are genuinely valuable and which are ritualized execution being automated.

Here's how to adapt:

- Write out the problem before opening design software. Force yourself to articulate what you're solving and why. If you can't explain it clearly, you're not ready to design a solution.

- Practice explaining one design decision without visuals. Can you make someone understand your reasoning through words alone?

- Measure outcomes, not reactions. Evaluate based on whether your work made the user's task easier, faster, or less error-prone.

- Treat AI outputs as hypotheses to evaluate, not solutions to ship. Your job is to judge whether they solve the actual problem.

- Get comfortable saying no to good-looking solutions that solve the wrong problem. This is where human judgment matters most.

These aren't new skills. They've always separated strong designers from weak ones. They were just easier to avoid when execution skill could mask their absence.

The Real Threat Isn't Replacement

AI will not replace designers as a profession. What AI will replace is comfort. The ability to hide weak thinking behind strong execution. The security of being "good enough" at execution that no one looked deeper.

The future belongs to designers who think in systems rather than screens. Who ask better questions than machines can generate. Who understand consequences rather than just interfaces. Who can explain their reasoning in ways that build trust.

AI isn't replacing designers. It's replacing the comfort of being average. It's forcing a reckoning with what design work actually is when execution becomes nearly free.

That's not a threat to the profession. It's a filter. The designers who thrive will be the ones who were always doing the real work. The ones who confused execution with thinking will find themselves competing with machines that execute faster and cheaper.

The question isn't whether AI will replace you. The question is whether you were ever doing the work that couldn't be replaced. And if that answer makes you uncomfortable, you can change what you're doing. You can develop the skills that matter. You can shift from executing patterns to making genuine decisions.

But first, you have to be honest about which one you've been doing.

Key Takeaways:

AI exposes the difference between design execution and design thinking. Real design work happens before the pixels: framing problems, making strategic trade-offs, understanding context, and exercising judgment. The designers who thrive won't be the ones who master AI tools, but the ones who were already doing the cognitive work that AI can't replicate. This isn't a threat to design as a profession, it's a filter that separates execution from decision-making.